Many articles about Lewis Carroll have been published throughout history, yet very few of them ever mention the famed author’s stuttering.

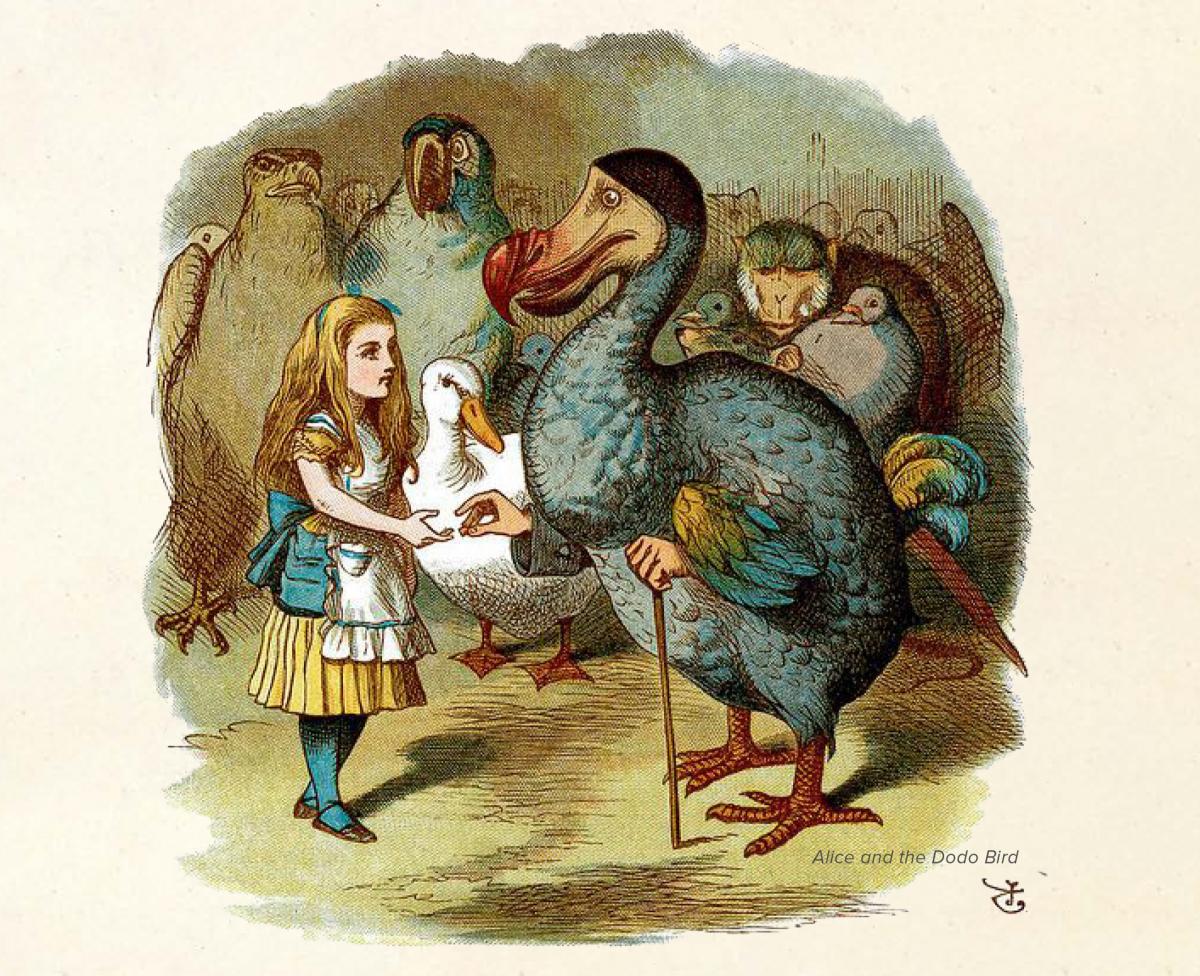

Recently, a May 30, 2020, article in MyModernMet.com entitled “5 Curiouser and Curiouser Facts About Fanciful Writer Lewis Carroll” cited his stuttering by stating that the character of Dodo in his famous work Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland came from his own inability to pronounce his real name of Charles Dodgson and frequently being forced to pronounce his surname “do-do-Dodgson.”

In Lewis Carroll: A Biography, author Morton N. Cohen stated, "The newborn son was the third of what eventually became a family of eleven children, and if these bloodlines deserve credit for the creative genius we know to be Lewis Carroll's, so perhaps they bear the blame for the stammer epidemic in Charles' speech and in the speech of much of his brothers and sisters."

In Lewis Carroll: A Biography, author Morton N. Cohen stated, "The newborn son was the third of what eventually became a family of eleven children, and if these bloodlines deserve credit for the creative genius we know to be Lewis Carroll's, so perhaps they bear the blame for the stammer epidemic in Charles' speech and in the speech of much of his brothers and sisters."

Lewis Carroll, the pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, was born in 1827 to Charles Dodgson and the former Frances Jane Lutwidge. In addition to being a writer, Carroll was a mathematician, a logician, an Anglican deacon and a photographer.

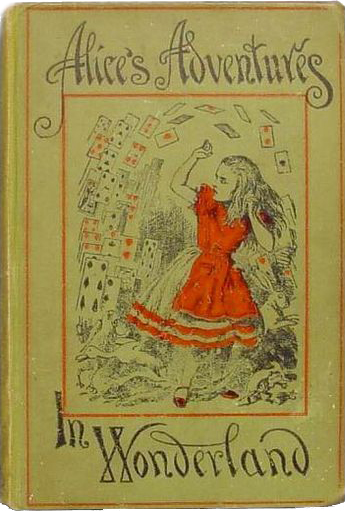

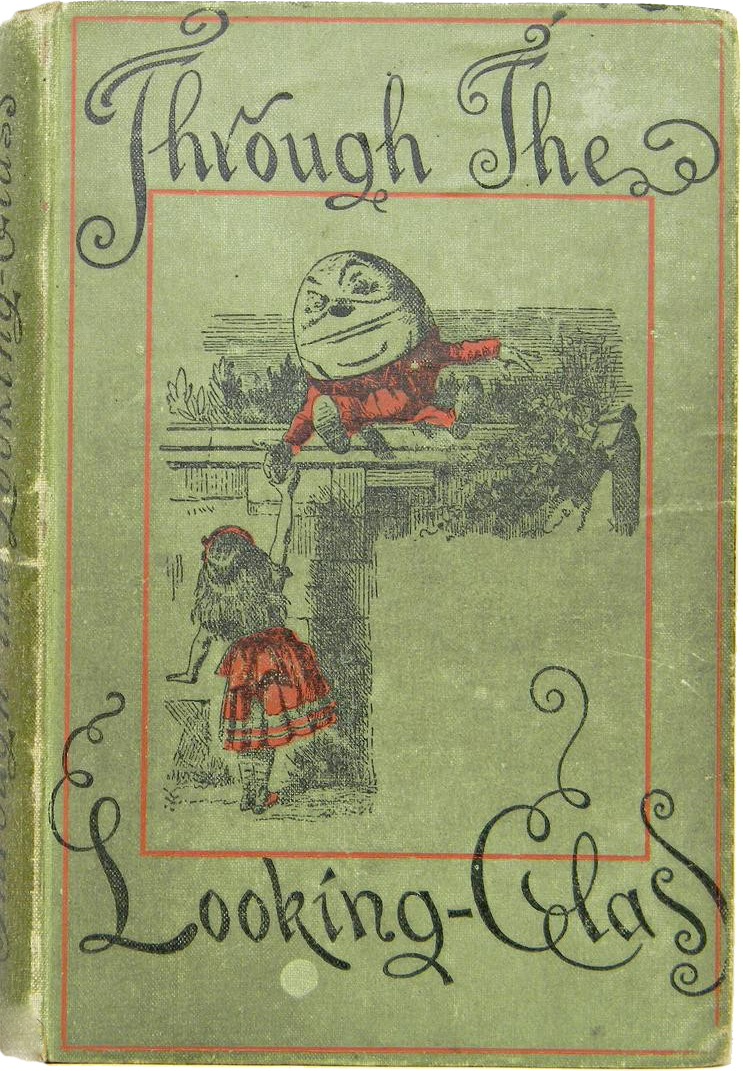

His most notable literary works are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, Jabberwocky, and The Hunting of the Snark.

Biographer John Pudney in Lewis Carroll and his World explains how childlike fantasies were not only the spark for Carroll's creative genius but also brought him into a new world where stuttering did not exist, “This perfectly hard crystal containing childhood was his true essential life, expressed in the Alice books and in some poems…When he spoke to these children, he lost his habitual stammer. He simply became one of them…This perennial childhood, together with the fantasy and poetry that sometimes expressed it, was his reality."

However, throughout the books, we can see several examples of advice that Carroll must have gotten as a child who stuttered.

However, throughout the books, we can see several examples of advice that Carroll must have gotten as a child who stuttered.

In chapter two, the Red Queen suggests that Alice should open her mouth "a little wider" when she speaks; later in chapter four, Alice describes “a rather awkward pause as she struggles to begin conversation. These are just a few of many excerpts that may have described the agonizing moments Carroll felt as he wrestled his own stuttering blocks.

In 1859, Carroll undertook speech therapy lessons from James Hunt, who was considered the foremost speech correctionist in Great Britain at the time; he was estimated to have treated 1,700 people who stutter.

In The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, biographer Jenny Woolf states that Hunt boasted he taught the patient to speak consciously in a way that other men spoke unconsciously.

Nothing bothered Carroll more about his speech than how it affected his ministry in the Anglican Church. His father had been an Anglican priest, and Carroll himself became a deacon. Upon one occasion he accepted the invitation to preach and recalled, "I got through it all with great success, till I came to read out the first verse where the two words 'strife, strengthened' coming together were too much for me, and I had to leave the verse unfinished."

Nothing bothered Carroll more about his speech than how it affected his ministry in the Anglican Church. His father had been an Anglican priest, and Carroll himself became a deacon. Upon one occasion he accepted the invitation to preach and recalled, "I got through it all with great success, till I came to read out the first verse where the two words 'strife, strengthened' coming together were too much for me, and I had to leave the verse unfinished."

Stuart Dodgson Collingwood (Carroll's nephew) wrote that his uncle "…saw that the impediment of speech from which he suffered would greatly interfere with the proper performance of clerical duties."

One longtime friend, May Barber, described Carroll's speech, “Those stammering bouts were rather terrifying. It wasn't exactly a stammer because there was no noise, he just opened his mouth.” When he was in the middle of telling a story ''…he suddenly stopped and you wondered if you had done anything wrong. Then you looked at him and you knew that you hadn't, it was all right.”

Biographer John Pudney wrote, “Perhaps his failure to correct his speech impediment was the overarching symbol of his entire life. He learned to live with his stammering; he knew what it permitted him to do, what not, where it would snare him and destroy the effects he sought to achieve and how to avoid the traps.” We see some evidence of this as Alice enters into a world that becomes “curiouser and curiouser” yet manages to avoid the snare and traps that Pudney describes.

Stuttering did not stop Lewis Carroll. He brought to life many lasting and imaginative stories for children. His own struggles and family history of stuttering are not as well known as they should be to further inspire children who stutter.

We find multiple instances of how Carroll may have written about his stuttering (and the people with whom he spoke) in Alice in Wonderland. Several striking examples are found in dialogue between Alice and the Red Queen:

" 'She can't do Subtraction,' said the White Queen.

'Can you do Division? Divide a loaf by a knife—what's

the answer to that?' 'I suppose—' Alice was beginning,

but the Red Queen answered for her.

'Bread-and-butter, of course.' "

“Curtsy while you’re thinking of what to say.

It saves time.”

“'It's time for you to answer now,' the Queen said,

looking at her watch, 'Open your mouth a little

wider when you speak...'”

"Look up, speak nicely, and don't twiddle your fingers"

"Think before you speak. Write it down afterward!"

Alice also receives communication advice

from Tweedledee and Tweedledum:

“The first thing in a visit is to say ‘How d’ye do?’

and shake hands.”

Taking a Closer Look

|

| Even though the mainstream media rarely mentions that Carroll was a person who stuttered, his family history gives credence to the discovery of the genetic link to stuttering. Carroll was born to parents who were first cousins; almost all of their eleven children (three girls and seven boys) struggled with stuttering past childhood. Citing Lewis Carroll's family lineage, Dr. Dennis Drayna explains how stuttering can sometimes be genetically traced through a family line. |

Generally speaking, cousin marriages present a risk for the occurrence of so-called recessive genetic disorders. Recessive disorders are those in which usually asymptomatic carriers of a disease gene produce a child that unluckily gets the bad gene from their mother and the bad gene from their father. Thus, they have no good copies of the gene and they then develop the disease. Most recessive disorders are quite rare, but some are more common.

For example, in the United States, about 1 in 24 individuals is a carrier for the mutant gene that carries cystic fibrosis. Since CF carriers are asymptomatic, occasionally two carriers mate and produce offspring, some of whom may inherit a mutated copy of the gene from both parents, thereby becoming afflicted with CF.

While the Carroll family situation is remarkable, families (with all offspring that stutter) are not unheard of. We’ve found many families in Pakistan in which cousin marriages have resulted in many siblings who stutter. We found a polygamous family in Cameroon, West Africa, in which a local chief had three wives and 22 children. We documented stuttering in 18 of them. So, in general, the genetic factors that contribute to stuttering can exert very strong effects.”

The genetic factors that contribute to stuttering are likely numerous, and they display complex inheritance problems. Thus, the great majority of familial stuttering occurs in small clusters, such as two siblings, a parent and offspring, an uncle and nephew, etc., but not as a clear recessive, dominant or other simple inheritance pattern.

From the Fall 2020 Magazine

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library