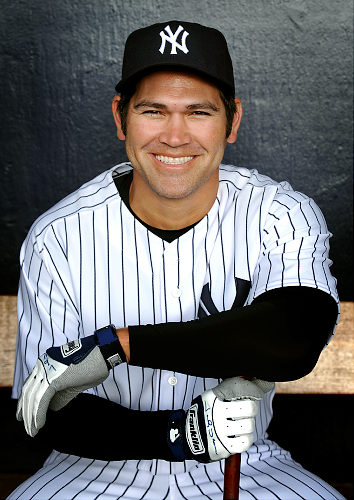

Johnny Damon, a two-time all-star major league baseball player, has won two World Series championships with the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees. Damon is well versed in talking to reporters and gave hundreds of interviews in the clubhouse after games, so it may come as a surprise to many to hear that he also struggled with stuttering.

Johnny Damon, a two-time all-star major league baseball player, has won two World Series championships with the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees. Damon is well versed in talking to reporters and gave hundreds of interviews in the clubhouse after games, so it may come as a surprise to many to hear that he also struggled with stuttering.

According to Sports on Earth, “Damon distrusted talk, having had a debilitating stutter as a child. Even now, at age 40, he made a point of talking slowly, pausing for a long moment before he answered each question, putting all his ducks in a row before he spoke.” "I thought too much as a kid," Damon said. "I'd talk without knowing what I was saying. I had to learn to slow my words down."

In 2006, Damon told The Daily News that speaking wasn’t always so easy for him. For several years as a child, Damon said he stuttered so badly he was afraid to introduce himself, for fear of cruel teasing from other kids. Damon vividly recalled going to the movies as an oversized kid and trying to pay the child's ticket price. When the theater clerks saw his frame - he was 6’-1”, 185 pounds by age 12 - they thought he was joking. Then, when they heard him stutter as he tried to explain that he was just big for his age, they thought he was lying.

"My mind was going a thousand miles an hour and my mouth would say whatever came to it," Damon recalled. "I slowed down, took my time, connected my words and got better. Now I'm talking in front of millions of people a day. At times, there's some slight hesitations and whatnot, but I feel like I've overcome it. I don't think about it too much anymore. I just roll with it and feel like I've come a long way.”

In a 2006 profile in The New York Post, his brother James Damon said “…he was a very shy kid. He had a stuttering problem, so he didn’t like to talk. It’s weird to see him speaking a lot now. He never liked to be in the spotlight because he was embarrassed.”

According to The Post, Johnny idolized his brother James as a child, who was a standout athlete. Damon then got into sports to emulate his brother. Damon went on to become a star player on his high school’s baseball and football teams, but he stopped playing football after his sophomore year to focus exclusively on baseball. He became one of the top prospects in the country during his junior season, and scouts flocked to his games.

Damon quickly became a local celebrity; before his first at-bat of his senior high school season, the announcer introduced him as the “number one player in America.” The pressure may have gotten to Damon that year, as his statistics slumped. After being projected to go No. 1 in the 1992 amateur draft, Damon slid to 35th. The Kansas City Royals ultimately picked him between the first and second rounds of the official draft.

He quickly recovered, however, winning the player of the year at each level of the minor leagues he played in. On August 12, 1995, he made his major-league debut against the Seattle Mariners at Kauffman Stadium. He went 3-for-5 with an RBI, run scored and a triple, and a star was born.

Damon was due to become a free agent after the 2001 season, and he was traded to the Oakland Athletics in January of that year. He was viewed as the missing piece that could get the Athletics past the Yankees in the playoffs. He joined greats like Jason Giambi and Miguel Tejada on a team that won 102 games, but ultimately fell to the Yankees again that year in the playoffs.

He would leave the Athletics’ after one season, signing as a free agent with the Red Sox. He soon became a fan favorite, and the Red Sox went on to beat the Yankees in the 2004 playoffs and continued on to win the World Series. The shaggy-haired, bearded Damon became an icon in Boston.

While gearing up for the playoffs in 2004, Damon spoke to The New York Times about his struggle with stuttering. "When I was younger, in first grade, I stuttered a lot," Damon said. "A speech therapist helped me out. It was a problem. I had friends tease me a little bit, but I think I got the last laugh right now." Damon said he still stutters, occasionally. "Sometimes, I think a little bit too much before I - I start talking before I think about what I'm going to say," he said. "So, sometimes, that's where the stuttering comes into effect. I never stutter when I sing. That was a way to kind of get over the anxiety or whatnot."

Fans were shocked to see him go when he joined the Yankees in 2006, but he went on to win over New York fans and take home a World Series title with the team in 2009. Damon was still on the Yankees in 2010 when the film The King’s Speech came out. In a 2011 interview, Damon told The Boston Herald he related to King George VI’s plight, and that he understood the methods he had to use to alleviate stuttering.

Those close to Damon told USA Today that his transformation from “stammering speaker to media magnet” speaks to his determination and self-esteem. USA Today noted that although he downplays the stutter, Damon doesn't hide it. He says a speech class he took as a child helped him, but the problem lingered through much of his professional career. Damon also revealed that he was the subject of some clubhouse bullying in his early days with the Kansas City Royals.

Damon told The Daily News he started taking speech therapy classes in second grade because he had trouble saying " 'S' or 'T' or 'D'. He could sing without stuttering - mostly songs by hair bands such as Motley Crue, Damon shared, laughing - and that helped build confidence. "When I was able to talk a lot and express my feelings, I think that's what really helped," Damon said. "I even dealt with this in my first couple of years in the big leagues and it's something that I still have. Obviously, when I talk now, there are 'ums' and slight hesitations to help me get past it. "Sometimes I got teased and maybe people didn't understand," Damon said. "They thought I was a little slow or just couldn't really talk. Playing my sports did my talking and who's laughing now?”

"I learned how to overcome it by talking slower, by re-collecting my thoughts, because my brain goes 100 miles an hour," Damon said. "It was a big deal." According to The Orlando Sentinel, Damon now works with the Lake County, FL. Sheriff’s Department to help stop bullying in schools.

"A lot of kids work their way out of stuttering by being good at sports," Stuttering Foundation president Jane Fraser said. "It gives you self-confidence. And then the more you talk, the more you will get out of this problem. I think that sports analogies help kids who stutter. You've got to work on your speech. We tell kids, 'Don't think someone who can hit a baseball is an expert because they just do it five minutes a day.’”

Damon’s determination and will to succeed is an example to all younger children and teens who have struggled with stuttering. He did not let his struggle with stuttering prevent him from having fun and doing what he loved, even though his job often required talking to reporters and speaking in public.

"I always thought I had a stuttering problem and people would stay away, but I guess because I overcame it, I tend to draw people into me and people want to hear me speak now," Damon told The Daily News. "And that's pretty amazing.”

Posted May 22, 2015

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library