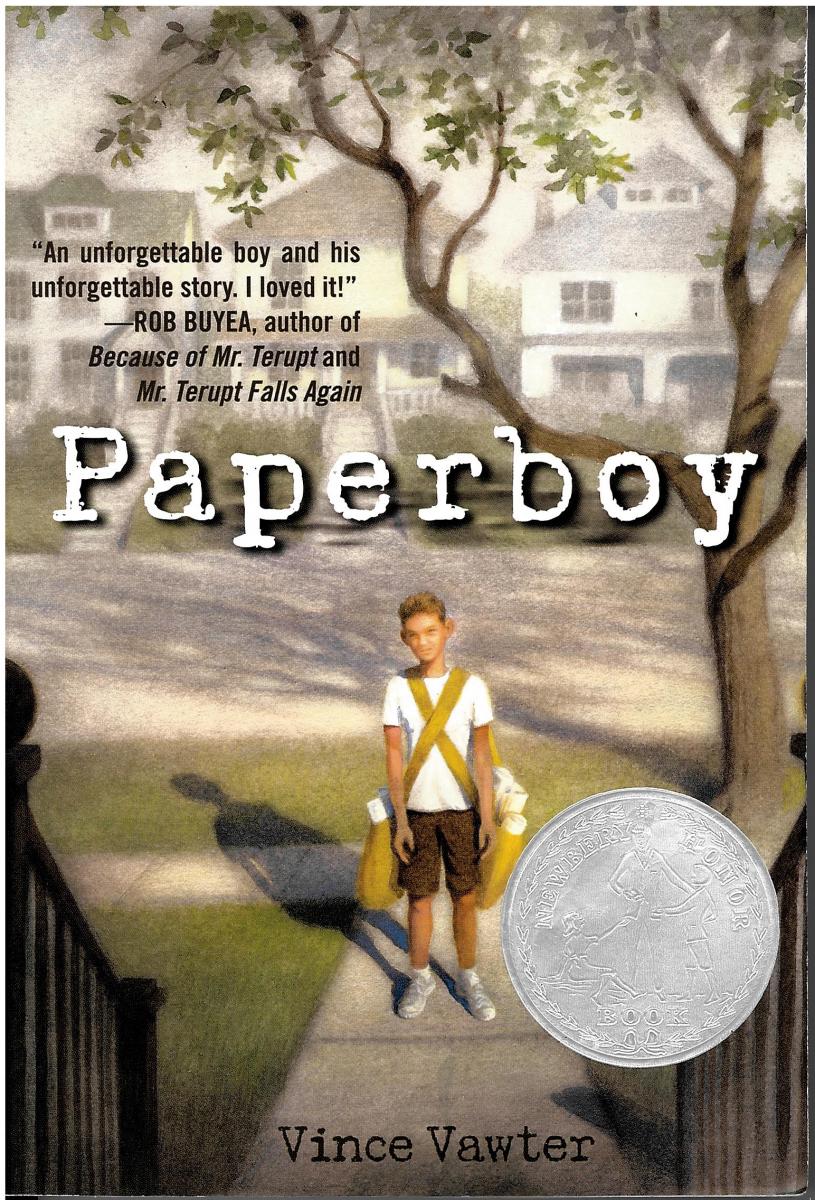

Paperboy was our Stuttering Foundation Summer Book Club pick for 2020. Author Vince Vawter graciously joined Sara MacIntyre, M.A., CCC-SLP, for a Live Q&A in August. A recording of the full video interview is available on our Streaming Video Library.

Paperboy was our Stuttering Foundation Summer Book Club pick for 2020. Author Vince Vawter graciously joined Sara MacIntyre, M.A., CCC-SLP, for a Live Q&A in August. A recording of the full video interview is available on our Streaming Video Library.

SARA: We had tremendous feedback from readers, so many great questions submitted, so thank you so much for joining us today. One of the most common questions, and maybe a great place to start would be, what inspired you to write Paperboy?

VINCE: Somehow I knew I was always going to write this book. That goes way back 20 or 30 years. I knew I had a story to tell, and I kept waiting for somebody else to tell it like it should be told. I could never find that. When I retired from newspapers, I said, "Well, I'm going to write this book. I don't know if anybody is going to read it, publish it. But if I can make one person feel less lonely with what they are going through with their stutter, I think my book will be a success."

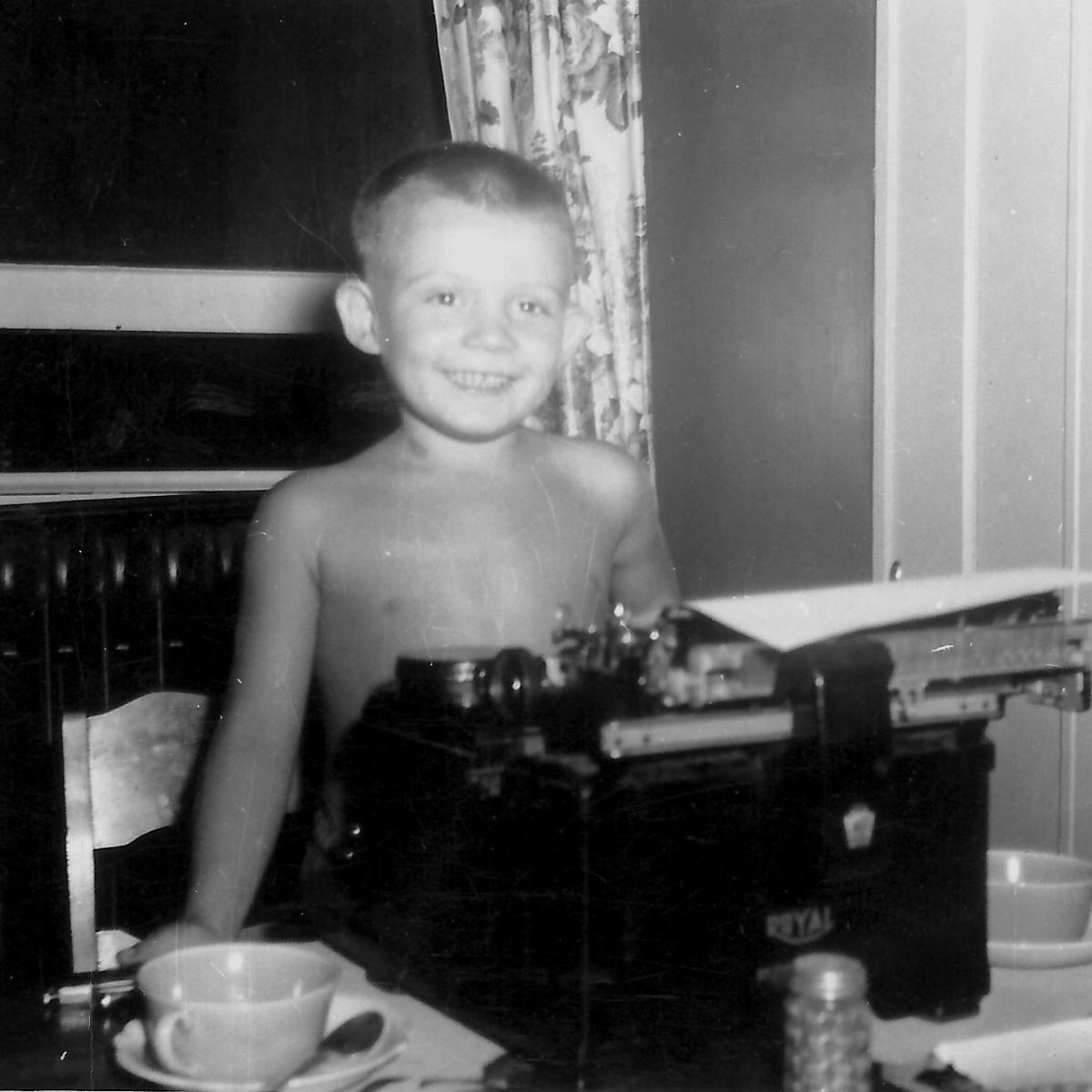

I had no idea it would receive the reception it did. I couldn't imagine it. I'm thankful every day that I got a chance to tell my story the way I wanted to tell it. I don't want to seem haughty about this, but I'm not sure anybody else could have told this kind of story. Much of the book is autobiographical, especially in Paperboy. In Copyboy, it draws a little bit more on the fiction, but the story is the story of my childhood. I still can't answer the question, how my younger years are with me so closely. The only thing I can figure out is that it was such a traumatic time in my life, that it affected me, and it stuck with me.

I had no idea it would receive the reception it did. I couldn't imagine it. I'm thankful every day that I got a chance to tell my story the way I wanted to tell it. I don't want to seem haughty about this, but I'm not sure anybody else could have told this kind of story. Much of the book is autobiographical, especially in Paperboy. In Copyboy, it draws a little bit more on the fiction, but the story is the story of my childhood. I still can't answer the question, how my younger years are with me so closely. The only thing I can figure out is that it was such a traumatic time in my life, that it affected me, and it stuck with me.

While I can't tell you what I had for lunch yesterday, I can tell you about certain days in 1959 when I had some trouble saying my name or whatever. I'm so thankful that I got a chance to tell my story the way I wanted to.

S: And we're all so thankful that you were able to. We received countless emails this summer from readers reflecting on how impactful this book and this story was for them—from parents, people who stutter of all ages, as well as a large number of speech-language pathologists. You really had an unbelievable way of bringing the experience of stuttering to life.

V: I think one of the things I'm proudest of is I know a lot of speech-tlanguage pathologists are using this in conjunction with their clients. I've got to tell you, SLP's are my heroes. My approach to stuttering (if I were an SLP) would be to treat or take into account the whole person, not just the stuttering person. I think that this book that might help an SLP do that.

S: Another question that was frequently asked relates to what was true in the book based on your personal experience. Could you reflect a little bit on what key aspects within your experience as a person who stutters really were weaved through into the story?

V: Right. Well, one easy way to answer that is that everything in the book which had to do with stuttering, was factual. I had trouble saying my name, and on more than one occasion, I would pass out because I held my breath too long trying to say my name. If you remember the scene where the boy is in the restaurant with some of his parents’ friends, and he gets embarrassed, and it all just starts coming onto him and he loses his spaghetti all over the table and everybody? That actually happened to me. Jane will know the restaurant, it's Grisanti's Restaurant.

V: And then I mentioned in there how I would keep a thumbtack in my pocket, and any time I had to speak in class, read aloud in class, I would jam that thumbtack into the palm of my hand, wanting the pain of that to take away the pain of stuttering. And of course, it never did. Everything in the book that had to do with my speech impediment, was real.

Now, all the characters, except for one character were right out of my childhood. That's about the only way I could write it, I found out. I think in my newspaper background, I think I have trouble straying from facts. So, the story I wanted to tell, was the one I lived. The reason the fiction is in it is because I had to have Mr. Spiro, who is the fictional character. I had to have him in there to pull everything together. To have a mentor to lead me, and it's a mentor I did not have at that time. I had some later, but I didn't have it then.

S: Yes, your relationship with Mr. Spiro has come up frequently in reader comments and questions. Who was that character to you? What did he embody?

V: We were up in New York, and the Random House lawyers had found out that the book was based a lot on my childhood, and so they had to vet the book. They went through with me on each of the characters, if they were alive or dead, everything. They came to Mr. Spiro, and I said, "Well, you don't have to worry about him, he's completely fictional." My editor looked across at me and she said, "I know who Mr. Spiro is," and I looked at her and I said, "What do you mean?" And she said, "Mr. Spiro is the mentor you never had, and the one you needed so badly. And plus, there's a lot of you in Mr. Spiro now." I had not thought about that, but the more I thought about it, I think the more that she was right.

V: We were up in New York, and the Random House lawyers had found out that the book was based a lot on my childhood, and so they had to vet the book. They went through with me on each of the characters, if they were alive or dead, everything. They came to Mr. Spiro, and I said, "Well, you don't have to worry about him, he's completely fictional." My editor looked across at me and she said, "I know who Mr. Spiro is," and I looked at her and I said, "What do you mean?" And she said, "Mr. Spiro is the mentor you never had, and the one you needed so badly. And plus, there's a lot of you in Mr. Spiro now." I had not thought about that, but the more I thought about it, I think the more that she was right.

S: This comment from Michelle really resonates, "As an SLP, I aspire to be a Mr. Spiro to my clients." What kind of characteristics do you feel like SLPs honoring Mr. Spiro's role in your journey would embody?

V: When I started out on this book tour, I was a little afraid that I would offend professionals. I am not an SLP, but one of the things I truly believe is that our goal (instead of some kind of a perfect fluency,) should be to find our voice. I think that Mr. Spiro would say that as long as you can say what you want to say, when you want to say it, don't concern yourself about the quality. Concern yourself about what you want to say. I think this idea that we all have to come out of this with perfect fluency, or with... I don't know, 90% fluency, 80% fluency, whatever...I just don't think that should be what the journey is about. I think it should be finding your voice, with the help of your SLP, with the help of self-therapy, with some guts, some practice, whatever you have to do. I don't think any of our journeys will be the same.

I stayed with what I considered a stuttering problem through college, well into my career. And then through organizations like Stuttering Foundation, through a lot of other things, I kind of found my path to find my voice. I can't tell you how much I stutter now. I do not know. Just because I pay attention to what I want to say, not how I'm going to say it. I do some things now which I'm sure some SLP's out there would not agree with. I still do some word substitutions. I still do gentle onsets sometimes. I'm not sure what they're called now, they're probably called something else now. I find things which let me say what I want to say. I think the SLP's who take a holistic look at this, I think that those are the ones that I applaud the most.

In the past few years, I've been reading an awful lot about the covert stutterer. I should have been the poster boy for covert stuttering. I tried to hide my stutter in every way I could. I would lie about it, I would skip class, I would do anything. I would pretend I was sick; I would do anything not to have to speak in class, or in some social situation. What that did is it held me back from starting on my journey of finding my voice. I just would not admit to myself that I stuttered so badly, and I had all these blocks, and I was fearful, and I would kind of change who I was. That's just not the way to go about it.

S: If you reflect back, how do you wish your family had supported you? Do you have any hindsight wishes there?

V: Yes, I do. My stutter was never talked about. It was the elephant in the room that no one talked about. I didn't want to talk about it. My parents, I don't blame them. Stuttering is very complex, it's a complex situation. I shouldn't have expected them to understand my stutter. Speech therapy at that point, it was in its early stages, it has improved immensely from then thanks to people like Jane. We have come so far.

The one thing I would say is you have to get your stutter out on the table. You have to talk about it. It's hard. It's hard, I speak to a camp for young people who stutter now and it's hard to tell a six or seven-year-old that, "This is not going to go away overnight. There is no magic pill. You have to have courage, you have to put yourself out there. You have to fail. You have to come to grips with the fact that, yes, while you have a stutter, there's nothing wrong with you. It's perfectly normal." It's a hard message, but I think this is where the SLP's come in. It's a slow process, it changes for everybody. They're on their own journey. They have to find their own way with some help.

When I was in school (I went to a small, private school), they were concerned about me. I know they cared for me and I know they loved me, but they did the exact wrong thing. They would skip over me in class. They would let me slide. That's just not the right thing either. I had a few teachers in high school, I had one in high school, and then I had one in college who challenged me to step out of my comfort zone. I'm telling you, I was mad as I could be at them then.

"Why won't you let me skate? Why won't you let me get by with this?" But they had the confidence in me to let me fail, almost to the point of where they made me fail. I worship them to this day. It's tough but you can't let it hide inside you.

S: I think that's such an important message for SLP's and parents to understand, the importance of allowing someone to "fail.” Really to face it, and I think a lot of the attempts by SLP's to “save,” or keep clients “safe” by solely providing strategies and reinforcing that fluency is more important—actually keeps people from getting to the ease that they can enjoy with communication by facing it.

A teen asks, “I noticed you don't say your name until the end of the book. Was there a specific reason you waited until the end? Because saying your name is one of the most important things we have to say, even though we can try to avoid it, we can't. I struggle with it. Does this have anything to do with why you kept it until the end of the book?"

V: It's got everything to do with it. Saying my name was my albatross. At the start of school each year, I would start going into sweats, about the middle of August. School would start the first of September, I'd start worrying about it in August because I knew the teachers would say, "Okay, everybody stand-up, tell us your name. Tell us your brother and sister’s names. What your pet is, and what you did this summer." I'd have rather been whipped 40 lashes than do that.

I always knew that that was going to be a culmination of the book. I didn't know how I was going to get there, but I knew that would be the culmination of the book. I had to be careful with my editors, because I didn't want anybody to think that on the first day of school in the seventh grade, Victor Vollmer got up and he said, "My name is Victor Vollmer, and I'm cured." Or anything like that. I wanted it to be where he stuttered but he was willing to stutter, and he knew he had to stutter to start on his journey.

S: There's a question here from a school-based SLP. "I find that as an SLP in the public schools, many teachers need support in understanding how to support students who they have who stutter in a way that helps them embrace stuttering, rather than allow them to hide inside. I struggle to support my teachers in this effort, I'm happy to share this book to help them see your story. Thank you, but any advice for me?"

V: Well, I get that question quite a bit, and I wish I was smarter than I am. My advice is when a teacher learns that they have a student who stutters, if they could go to that student, and say, "I want you to be comfortable in my class, because I know you are not going to learn if you're not comfortable. So what I'm going to do is, I'm going to call on you just like everybody else, but while I want you to challenge yourself, if there is a day and you are overwhelmed, and you feel like you just can't handle it, just give me a sign. Or just wave me off, and then I'll go onto somebody else. But I'm not going to stop calling on you. I want you to challenge yourself."

And then, you make sure they know that it is guaranteed that no one in the class is going to laugh at them. I think that's about the only way to handle it.

S: Speaking of your journey, there's more questions related to Mr. Spiro’s character and what he represented that you felt you did not have at the time. You mentioned some real-life mentors that later on did impact you and combined to be some of your inspiration for Mr. Spiro. Could you share anything or any experiences specifically from those?

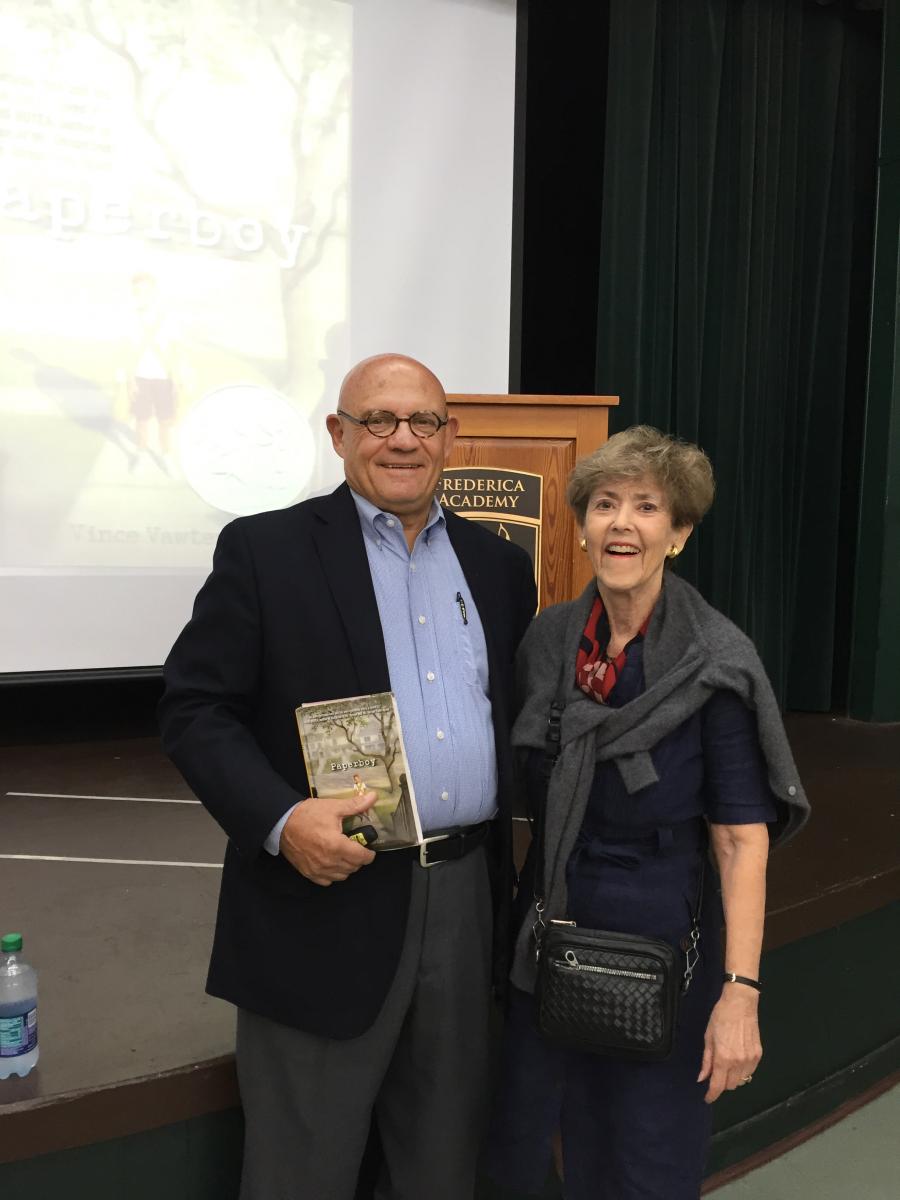

V: Well, one's sitting right here. Jane Fraser. I started studying her father. Her father was the founder of the Stuttering Foundation, and I looked at his life. He was in the parts business, and my family was kind of in the automobile business. So, we had a connection there. I did a lot of self-therapy through the Stuttering Foundation books. Here's the sad thing, I was so caught up in myself that the premiere speech organization in the country, I guess the world, was a few blocks from where I grew up. It took me so long to take advantage of it.

V: Well, one's sitting right here. Jane Fraser. I started studying her father. Her father was the founder of the Stuttering Foundation, and I looked at his life. He was in the parts business, and my family was kind of in the automobile business. So, we had a connection there. I did a lot of self-therapy through the Stuttering Foundation books. Here's the sad thing, I was so caught up in myself that the premiere speech organization in the country, I guess the world, was a few blocks from where I grew up. It took me so long to take advantage of it.

It's all a part of this, not wanting to admit that I stuttered. They're my heroes. To bring the problem of stuttering to a fluent community is very difficult because it's such a complicated world. It takes some scholarly involvement, it takes some therapeutic involvement, it takes a lot of training of SLP's, it takes continuing research. I look at SLP's now and the thing I'm most proud of is that a lot of SLP's stutter. I think that's great. I couldn't be more proud of them. It's what we need to do, we need to get it out on the table. And then we can talk about it, and then we can work on fixing it.

And when I say work on fixing it, there are some people out there who stutter, and they're going to be a six o'clock news anchor, more power to them. But there are some people out there who are going to stutter, and it's going to hold them back some. But they need to find that voice, whatever it is, and do whatever they can. I think it's almost like just going off that high dive. You dread it, you dread it, you dread it, but sometimes you just got to do it. And you find out, "Hey, it didn't kill me, so I'm going to try it again."

It takes good organizations; it takes families who are willing to invest some time in learning about stuttering. And then it takes some gumption, it does.

S: Would you say that writing your two books helped you the most on your way to embrace your stuttering?

V: I thought about that question a lot. I didn't mean for it to be a cathartic. I truly didn't. I just wrote it just to tell my story in case I could help somebody out there who was going through the same thing. But I'll go back to another story. I was speaking at a middle school, a large crowd, three or four hundred students, and there was this young lady in the front row. I could tell that she was hanging on my every word. You can kind of spot people like that, and I knew I was going to get a question from her.

Sure enough, when I asked for questions, she raises her hand, and I called on her, and she said, "Do you think you would have written your book if you had not stuttered? If you had not been a person who stutters?" And it was the first time I'd ever had that question. I thought, and I said, "Well, I'm going to give you an honest answer on this. No, I don't think I would have written this book." I thought I had satisfied her but no, she was going to come at me again. She said, "So you can say in a way, you're glad you stutter." I kind of choked up a little bit, and then I went back and I told my wife, I said, "I have just gotten about $3,000 in therapy in one little speech at a school..." I'm not going to say I'm glad I stutter, that's just not right. But I'm glad who I am because of my stutter. It's been a thrilling journey; I can say that.

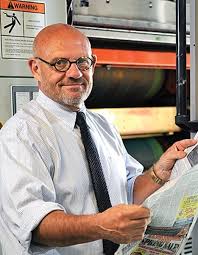

Vince Vawter, a native of Memphis, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (Ind.) Courier & Press. In 2002-2003 he was president of the board of directors of the Hoosier State Press Association. He previously served as managing editor of The Knoxville (Tenn.) News Sentinel and news editor of the now-defunct Memphis Press-Scimitar. Vince’s debut novel, PAPERBOY, received a Newbery Honor award in 2014. The story is based on his real-life experience growing up in the 1950s as a person who stutters. Vince spends his retirement traveling the country and discussing his books with schools, reading and education groups, as well as stuttering advocacy organizations. He and his wife, Betty, live in Louisville, Tenn., on a small farm in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains near Knoxville. Vince can be contacted through his website: www.vincevawter.com.

Vince Vawter, a native of Memphis, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (Ind.) Courier & Press. In 2002-2003 he was president of the board of directors of the Hoosier State Press Association. He previously served as managing editor of The Knoxville (Tenn.) News Sentinel and news editor of the now-defunct Memphis Press-Scimitar. Vince’s debut novel, PAPERBOY, received a Newbery Honor award in 2014. The story is based on his real-life experience growing up in the 1950s as a person who stutters. Vince spends his retirement traveling the country and discussing his books with schools, reading and education groups, as well as stuttering advocacy organizations. He and his wife, Betty, live in Louisville, Tenn., on a small farm in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains near Knoxville. Vince can be contacted through his website: www.vincevawter.com.

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library